Last week, a three-judge court in North Carolina did the unthinkable: it struck down a state redistricting plan on partisan gerrymandering grounds. This plucky little court held, in light of the overwhelming factual record chock-full of crass and extreme examples of partisan behavior, that the plan violated the law. Doing the heavy lifting was a clause in the state constitution that stated, quite simply: “All elections shall be free.”

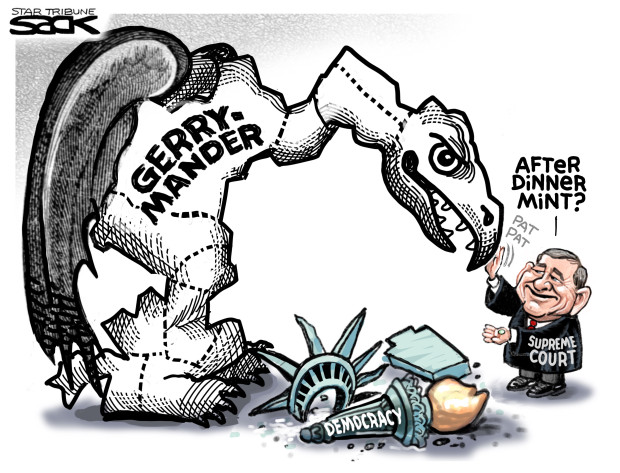

So here’s what we have. Five of the most “brilliant” jurists on the planet, who form the conservative majority on the US Supreme Court, cannot find a judicial standard that satisfies them. They agree that “[e]xcessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust.” More incredibly, they also agree that ” such gerrymandering is ‘incompatible with democratic principles.'” And yet, in the recent Rucho v. Common Cause, these justices could not find a judicial standard that satisfied them. In other words, gerrymandering, though in violation of “democratic principles,” may or may not be in violation of the US Constitution. They simply can’t tell. So they labeled the practice a “political question” and left it alone.

The easiest response is that their faux modesty is simply not believable. This is a Court as activist as any Court in history. Precedent means nothing to this Court, history even less, so long as conclusions and preferred outcomes must be reached. Think Shelby County. Think Heller. Think Janus. Just think.

And then comes the recent Common Cause v. Lewis. In case you don’t have time to read all 357 pages, I will simplify it for you: the three-judge court saw what everybody could see, a crass political gerrymander, and struck it down on state constitutional grounds. I’d say it was an easy thing to do, but the fact that the opinion spans 357 pages makes clear that this is no simple matter. But it is not, as the conservative majority on the US Supreme Court would have us believe, an impossibility, beyond their judicial capabilities. That point is simply not believable.

Thus begging the question: why the refusal to do the inevitable? Why the refusal to step in and reign in excessive partisanship and practices that the justices concede violate democratic principles? How to make sense of passivity in the face of clear harm, especially from a Court that is not passive about anything?

Or else: what do state judges know that Supreme Court justices do not?