A few months ago, while listening to a Freakanomics Radio episode about why rent control does not work, I heard things that made me think long and hard about our conversation in Bloomington, Indiana about affordable housing. Full disclosure: I don’t know anything about any of this. I am not an economist, nor am I an affordable housing advocate, or a developer. I am a citizen trying to understand a difficult issue. And here’s what I found. (Further disclosure: the debate as it’s been unfolding in Bloomington saddens me deeply).

The reflexive reaction to the lack of affordable housing is to call for rent control. But the laws of economics don’t agree that this is the right solution. As the podcast puts it, rent control “helps a small (albeit noisy) group of renters, but keeps overall rents artificially high by disincentivizing new construction.” Economic principles ask for something much more basic: either lower demand or increase supply. Sounds simple enough. The reason rent control does not work is that it stifles supply while doing nothing to affect demand. Thus, economists conclude that “rent control may be accomplishing a narrow, short-term goal — making existing housing more affordable for a select group of people — at the expense of the long-term goal of making a city more affordable generally.”

And so, the podcast asks, “what happens next?” Here’s an answer from Ed Glaeser, the Fred and Eleanor Glimp professor of economics at Harvard,

So, the big answer is, you need, as-of-right zoning that enables fairly high-density levels over a fair amount of space. So, currently Boston’s zoning plan is highly antiquated. Every project is handled on an ad-hoc basis. Usually, it involves variances that are quite high from the original plan, which means that they are highly subject to judicial challenge. All of that is a recipe for uncertainty and delay and endless community meetings.

The thing that works best is when you have something where you’ve decided in advance, “This is how much we’re going to allow to build; there are a couple of simple rules that you’ve got to follow. Come here, bring your units and make it happen.” And that’s what’s needed. That’s what actually works. It’s not something that involves a 10-year negotiation process, but something that says, “Here are the rules upfront. Go to it.”

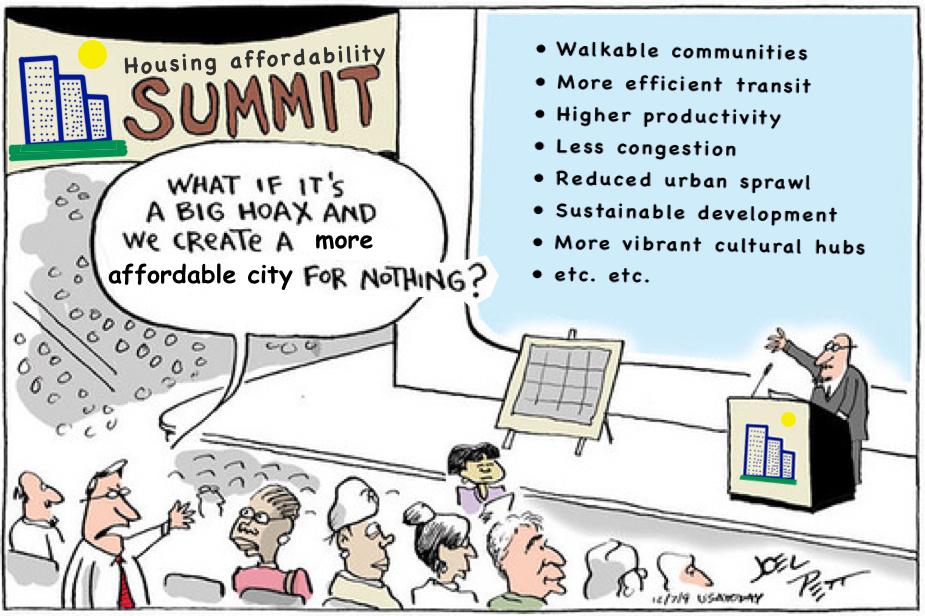

This makes sense. Create more supply while demand remains constant, and more people will be able to enter the market. The point seems almost unassailable. Happy to be proven wrong (see above: I already confessed my neophyte status).

This is not a new, untried idea. This past summer, Oregon passed a bipartisan bill requiring cities with over 10,000 people to allow duplexes in areas zoned for single-family homes. Portland goes further and requires cities and counties to “allow the building of housing such as quadplexes and ‘cottage clusters’ of homes around a common yard.” Other jurisdictions are responding similarly. Last December, Minneapolis eliminated single-family zoning throughout the city and to allow for duplexes and triplexes. California considered — yet tabled until 2020 — a housing bill allowing for quadruplexes in neighborhoods zoned for single families.

No such luck in Bloomington, Indiana’s “progressive” oasis. The mere mention of increasing density in “core” neighborhoods had people up in arms. And just this past week, our very own city council was beaten down by the forces of single-detached housing. And I am trying to figure out why. Why the vehement reaction to something that is being tried elsewhere as a way to create more affordable housing, what I consider to be a goal of progressives everywhere?

One argument is that high density housing will decrease property values. I cannot find any research on this point that so concludes. In fact, the opposite appears to be true:

Higher-density development can increase property values. Although location and school district are the two most obvious determining factors of value, the lifestyle benefits of high density communities can drive up their market value when done well. When there is a strong sense of community, or lots of amenities within a neighborhood, density and diversity can add a value of their own. Indeed, some experts believe that having multifamily housing nearby may increase the pool of potential future homebuyers, creating more possible buyers for existing owners when they decide to sell their houses.

This also makes sense. Increase demand for the land and it will be worth more. Importantly, according to the Urban Land Institute, the argument that “Higher-density developments lower property values in surrounding areas” is a myth. Instead, “[n]o discernible difference exists in the appreciation rate of properties located near higher-density development and those that are not.” Similarly, no study about the California housing market has found a reduction in property values as result of “affordable housing developments.” A recent academic paper states that “[w]hile the negative impact of density on housing values is a popular narrative, there is scant empirical evidence to suggest a negative relationship between density and residential property values.” And research out of MIT concluded that “mixed-income, high-density rental developments — so-called 40B developments – have no adverse effect at all on nearby property values.” So it appears that the property value argument is nothing but a canard. So there’s that.

Another common argument is that these missing-middle housing bills will not help in the climate fight. That also makes no sense in the abstract. It cannot be the case that sprawl, and people living away from their places of work, does not affect their carbon footprint. This also appears to be true:

The relationship between housing and transportation emissions is not complicated. The housing crisis in our cities and job centers — California is short 3.5 million homes, according to a report by the McKinsey Global Institute — is forcing more workers to “drive till they qualify,” the term used by real estate agents for what a growing number of Californians have to do to find housing they can afford. As cities that are job centers make it hard or impossible to build housing — for example, through de facto bans on apartment buildings in areas zoned for single-family homes — people who are priced out move further away, resulting in sprawl that covers up farmland and open space, clogs freeways and increases greenhouse gas emissions.

This also makes sense, and the research supports it. A recent study found that developing housing in what the researchers term “infill zones” — that is, zones close to school, work and housing and that place an emphasis on multifamily units — would result in a reduction of “at least 1.79 million metric tons of greenhouse gas reduction annually compared to the Baseline (business-as-usual) Scenario.” Such savings are akin to removing 378,000 cars off the road. The recent Fourth National Climate Assessment, released in November 2018, agrees. Some analysts argue that that the Green New Deal must include these missing-middle alternatives. (here’s another essay, for the most curious among you).

None of these facts mattered. In the end, those living in single-detached zoned areas spoke much louder than everyone else, and their voices carried the day. Only one city council member held his ground. I could say much more, about deliberative Democracy and how easily elected officials bent to the voices of the largely white, middle-class, home-owning crowd that made its intentions loud and clear. Who speaks for the poor, for those who were not there? Who speaks for the future? Who speaks for facts as researchers and scientists know them? Not the Bloomington City Council. And that’s sad.