I listened with great interest to a recent conversation in 538’s Politics Podcast about the political status of Washington, DC and, by implication, Puerto Rico. The title of the podcast asked, “Should Washington, D.C., Be The 51st State?” This is an incredibly important question, for reasons of politics, constitutional law, and democratic theory as applied to questions of sovereignty and citizenship. Unfortunately, and uncharacteristically, the podcast fell short. Careful listeners walked away confused rather than educated.

Why Statehood for DC? Why not?

This became clear at the onset, as soon as one of the panelists, Representative Eleanor Holmes Norton, answered the question of why D.C. should be a state. Her answer is important, not only because it fails to provide a clear answer to what should be a simple question, but also for how it reflects on issues that arise later in the conversation. She said:

“[D.C.] should have been a state long ago. It’s qualifications to be a state exceed those of most states. For example, the District is number one per capita in federal taxes paid to support the United States of America. The District is one of the oldest jurisdictions in the United States and it has 700,000 Americans and that’s about the equivalent population of six states. So the real question is, why shouldn’t DC be a state?”

The answer implicitly defines the qualifications for statehood. One is the payment of federal taxes; another is the age of the territory in question; and a third is the number of U.S. citizens living within the jurisdiction. It should be evident that these qualifications are not terribly helpful. Why are these three qualifications dispositive, and not others? We don’t know. How do these metrics fare when compared against historical practice? Not well (Hello, California and the old Louisiana Territory more generally). And to her own question, the answer is quite easy: because Article IV assigns this question to Congress, (“New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union”) which has yet to decide otherwise.

The discussion did not get much better from there.

DC and the Seat of Government Clause

The host, Galen Druke, then turned to the obvious next point: the Constitution, as understood and interpreted for generations, “says that the seat of government should not be a state.” The argument appears rock solid. Here’s the constitutional text:

“The Congress shall have Power To …exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States.”

The reason for this “indispensable necessity,” according to none other than James Madison, of Founding Father fame, is that Congress must have “complete authority” over the seat of government. Otherwise, he argued, “the public authority might be insulted and its proceedings interrupted with impunity.” History and general practice were also on his side.

How does Representative Norton respond to this important argument? Not very well. “It says no such thing and we needn’t get into constitutional law, and you are talking to a former tenured professor of law at Georgetown. So that’s not what it says.” I won’t lie. I was intrigued. Representative Norton was about to swim against a considerable historical constitutional tide. What then does the Constitution say on this issue? She immediately continued: “And every state that has entered the union did so the same way we’re trying to get into the union, by vote of the states.” So what then does the constitutional text say in reference to DC and the seat of government argument? We don’t know.

Nate Silver picked up on this and asked her, “in 90 seconds or less,” to tell us what the constitutional argument is, “because it is important for our listeners to hear.” Representative Norton took the question to mean, what is the constitutional argument for states to enter the union? But that was not the question in front of them. The question was, based on her initial reaction, whether the seat of government may also be a state. This is where the original question began, this is the reason why she proffered her credentials as a law professor, and this is the contemporary debate over DC statehood. Here is her non-responsive answer: “The way the states get into the union is that there needs to be a vote, the states need to come together the way we do in passes of legislation.”

It got worse: the host immediately turned to H.R. 51, a proposal that the House will vote on next month, on July 23rd. The proposal would not turn all of DC into a state, but instead, he explained, “the way that DC would gain statehood is by shrinking the actual seat of government to like the perimeter of some federal buildings, essentially leaving a seat of government that is not a state in order to satisfy that constitutional requirement.” This approach would then “mak[e] the vast majority of the district where most people live the actual state.” This is to say, the very proposal in the House accepts as true the argument that the seat of government must not be part of a state. Why Representative Norton suggested otherwise is neither clear nor accurate.

The conversation soon turned to the reasons for DC statehood. They discussed three reasons.

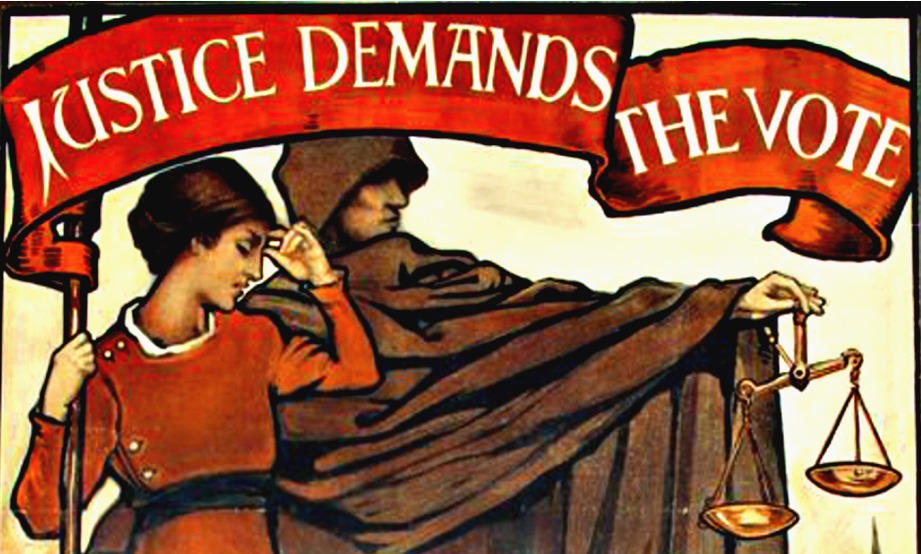

Voting Rights and “full American citizenship”

Congressman Steny Hoyer, House Majority Leader, argued for statehood as a way to provide residents of the district with a congressional representative. Only then will they have “control over their own interests” and be “full American citizens” (italics mine). I agree that statehood for DC is a fine idea. I also agree that voting rights ought to be an attribute of American citizenship. Assuming that we can agree on a definition of “full American citizenship,”however, the right to vote need not be conflated with the statehood question. This is clear the lesson of the 23rd Amendment, which extended representation to DC in the Electoral College. There may be reasons to turn DC into a state; conferance of the right to vote to its citizenry need not be one of them.

Equality

Congressman Hoyer stated numerous times that DC was home to 700,000 residents, all of whom deserved congressional representation. Towards the end of the podcast, he raised an “intellectual argument:” why should DC’s 700,000 residents be treated differently from Wyoming’s 500,000 residents, “in a country that talks about equality and justice and inclusion?” Congressman Hoyer also offered a legal argument: “that every citizen ought to be treated with due process and equally.”

These are obviously losing arguments. Congressman Hoyer is right to wish that citizens be treated equally. But this is clearly not the world we live in. In our constitutional world, citizens are treated unequally across the states as a consequence of our commitment to federalist principles. To live in California is not to live in Hawaii or New Hampshire. To be sure, DC residents are treated worse than all other states in terms of congressional representation. But this is a consequence of a prior choice made at the founding. Is he saying that the Constitution treats residents of DC unconstitutionally?

Consent Theory

Finally, Congressman Hoyer argued that the DC status question should be decided by DC residents, because “we we are a nation that believes in citizens having the choice.” And DC, Representative Holmes Norton made clear, “voted overwhelmingly to become a state.” This is an intriguing argument, though hardly dispositive. The wishes of local residents should play some role in the status question, so much is true. But that is only one consideration among many others. And the calculus and final decision have always been left, for better or for worse, to Congress.

Why not Puerto Rico?

Late in the podcast, Nate Silver agreed that “tactically, I can see why Representative Norton is skeptical about having Puerto Rico be part of this discussion, because they are very different cases. They’re very different cases.” I’m not really sure what that means. Let’s try to figure it out.

Representative Norton argued, first, that adding Puerto Rico to the DC statehood debate will “confuse people,” because “Guam, Puerto Rico, and the other territories . . . do not pay federal income taxes.” To her mind, “that really is a decisive difference.” This is a nonsensical answer. She is right to say that the people of Puerto Rico do not pay federal income taxes. What is less clear is why this point should matter. The people of Puerto Rico pay various other federal taxes, such as the FICA tax, which funds Social Security and Medicare. They also pay payroll, business, gift and estate taxes, among others. This is not insignificant. In 2016, as the island faced one of its worst financial crises, Puerto Rico contributed $3.6 billion dollars to the U.S. Treasury. Also, Puerto Ricans are not offered tax credits – such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit – which are available to citizens on the mainland. This is an important point; it means that, were they subject to federal income taxes, low income filers in Puerto Rico might be better off. The conclusion is clear: to say that they are a separate case because they do not pay federal income taxes is a sleigh of hand.

Further, DC presents a different case because some of these territories have “miniscule populations.” Puerto Rico does have a “big population,” Representative Norton conceded, but that was in fact a bad thing: “Puerto Rico is, the last time I looked, big enough to have six representatives, and the district is not so forbearing because it needs only one.” So Puerto Rico is not too small, but also too big. This is an argument only Goldilocks would appreciate. This is especially galling in light of the earlier argument about the disenfranchisement of DC’s 700,000 residents. How does one, in the next breath, defend the disenfranchisement of 3.6 million?

Third, Congressman Hoyer argued that the people of Puerto Rico must decide for themselves the status question, and they are yet to do so. Representative Norton underscored that this was not true of DC, which has expressed its preferences clearly. This is a fair enough point, though we should be careful in how far we extend it. If thinking about popular preferences generally, it is also true that the American public favors Puerto Rican statehood more than it favors DC statehood. The important point is that neither point should be determinative, nor the reason to consider the two cases as “very different.”

Finally, DC is part of the contiguous United States, in land that was once part of Maryland and Virginia. In contrast, Puerto Rico is a Caribbean island with a unique history, acquired by the United States as war bounty and located 100 miles off the coast of Florida. So yes, Puerto Rico and DC are different cases, both geographically and culturally. But are they different in a way that should matter for the status debate? That is less clear, if clear at all.

* * *

Here’s the most important point of all, which an inattentive listener might have missed. “We are not a colonial power, we don’t want to be a colonial power, we should not be a colonial power,” said Congressman Hoyer. This is the crux of the statehood debate, maybe for DC, but certainly for Puerto Rico. Yes, they present slightly different cases. But at their root, they raise the same issues. The status debate for Puerto Rico and DC raise questions of democratic theory, and what it means to be a citizen; of constitutional law, and whether the US Constitution allows for second class citizenship; and politics, in reference to how our political parties handle difficult questions of rights and sovereignty. Congressman Hoyer is right; we should not be a colonial power. The harsh reality is that the United States is exactly that. To be clear, this is not to say that statehood must be extended to DC and/or Puerto Rico. Rather, it is to say that the present status of both territories is unacceptable and must change.