A few weeks ago, Slate’s political gabfest discussed Mayor De Blasio’s proposal for amending entrance requirement to NYC’s “specialized high schools” — namely, Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and Brooklyn Tech. Students gain admission to these elite high schools by how they perform on one test that they take as 8th graders. But the test leads to tremendous racial disparities at these elite high schools. In response, De Blasio wants to admit the top 7% of students from high schools across the city.

This is a hard conversation, and liberals in particular have a difficult time talking about it. Race is hard, ascribing desert is hard, achieving justice is hard. I’m not even talking about fixing history and the effects of our racial caste system. I am talking about the disbursement of scarce public goods. This is what the debate over these specialized high schools in NYC asks us to consider. Yet this is something that the podcast hardly touched upon.

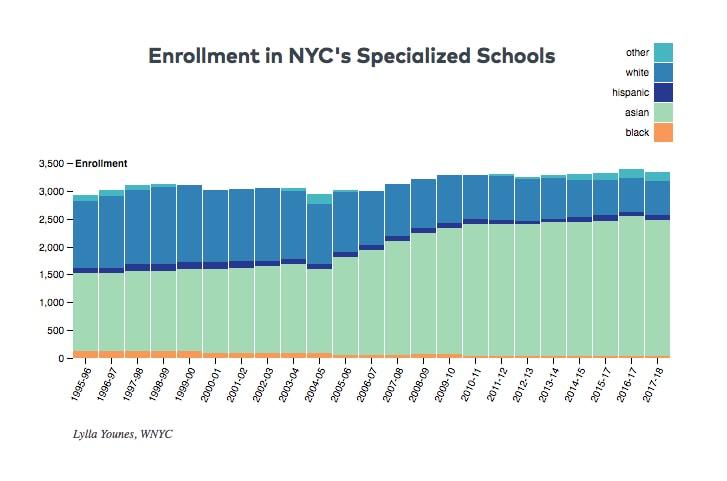

First, the facts. The racial composition of students enrolled in NYCs specialized high schools is abysmal. Take a quick look at the following chart:

Here are the numbers: in the three “highest-status schools” —Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and Brooklyn Tech — the Black and Latino populations are 4, 9 and 13 percent, respectively, which are below the 70 percent in schools across the city. The racial impact of the test is undeniable. The debate asks whether anything should be done about it.

The debate is really asking, if implicitly, about our conceptions of justice and desert. Students with the highest scores on the test deserve to attend these specialized high schools, and it is unfair to deprive them of this opportunity, for which they have worked so hard. This is particularly unfair once we consider that the students who most benefit from this opportunity, and who work hardest to achieve it, are poor Asian students. This is how David Plotz put it in the podcast:

[De Blasio’s proposal] has been met with real anger from Asian Americans who know that most of the Asian American students at these elite schools are from very poor backgrounds and that their parents have made huge sacrifices to help them achieve on the test and the students themselves have worked very hard to achieve at these tests.

These students deserve everything they got, and it would be unfair to take it from them.

This is an odd debate. To simplify: assume a school with 100 seats, and for which a million students apply. What is the just and fair way to allocate these seats? Could we defend an allocation as just that looks only to how students perform on one test, one time? Is it fair to compress the academic portfolio of an applicant to however the student performs on one particular test? Is it fair to reduce the applicant’s past and life experiences to the outcome of one test?

To ask those questions is to answer them. There is a rich literature on the “myth of standardized testing” and how we use tests as a way to label and sort students. We pretend that these tests are objective measures of student achievement. They are not. For any school to pretend otherwise, and to base life-altering decisions on the outcome of one test, is indefensible. Might as well ask applicants to climb Everest, or race Usain Bolt in a hundred meter dash, or better yet, ask for their parents’ contributions to the school, all in the name of just deserts. Once you are willing to base your decision on the outcome of just one test, anything is possible.

But the podcast almost went there. Jon Dickerson asked the right question: what is the goal of the schools? Is the goal simply to find the students who can best perform in these niche tests, to reward their academic dexterity as reflected in this one test? Or is the goal “some other set of values and desires?” That’s the right question. Unfortunately, it is much easier to come up with a test, label it “standardized,” and pat ourselves in the back as we deflect all criticism as undeserved and unfair.

So yes, way to go, Mayor de Blasio. This is a conversation worth having